The day after the 2016 presidential election, my parents were at the 7-11 in Central Garage, Virginia. My father saw a man buying a stack of newspapers proclaiming Trump’s victory, and he asked the man, “You like him?” Oh yes, the man said—he was very happy that Trump won. “Maybe you can meet him someday,” my dad said. “Maybe he can grab your wife by the p***y.”

My dad was born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. He grew up riding horses and having adventures with his brothers and cousins. He spent a lot of time with his grandparents in Lewisburg, and learned to drive when he was eleven so that he and his cousin Rudy could take their grandfather Charlie “gallivanting” every Saturday on the windy one-lane roads that snaked through the mountains. Dad and Rudy took turns driving Charlie’s ‘51 Plymouth while their grandfather drank vodka in the backseat or sat on the hood, shooting rabbits.

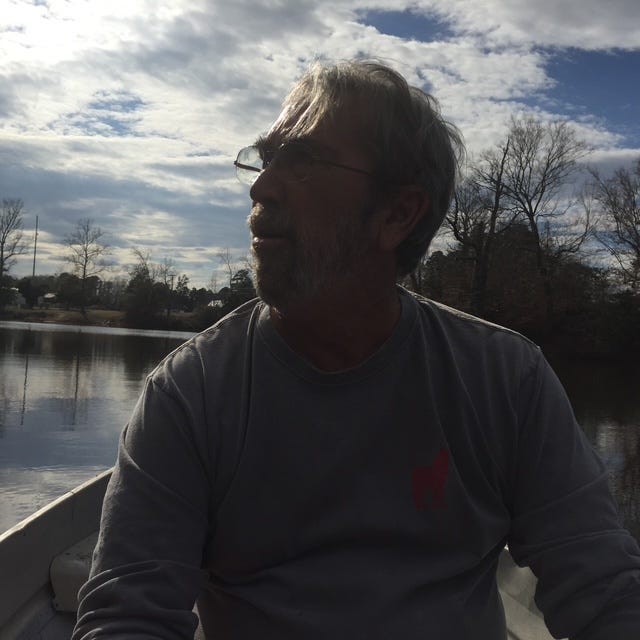

Dad grew up to be a hippie, and later a carpenter and contractor. You probably wouldn’t have called him a hippie to look at him in later life—he was a Southern white man who loved golf and sports and sometimes drove a pickup truck. But unlike some hippies he never forgot what it meant to oppose an unjust war, to be apprehended by police because you had long hair and rode a motorcycle, or to witness other people—women, African-Americans, other people of color—finally get rights that they should have had all along. He identified with working people because he was a working person, and he knew what side he was on and wasn’t afraid to share it. (He wasn’t afraid of anything, as far as we knew.)

Before this latest election, he’d sometimes encounter, through work, other white men who were Trump supporters. “I always thought you were smarter than that,” he’d say, shaking his head. With one guy, a plumbing supplier he saw weekly in Lynchburg, he said, “I want you to think of one thing Trump did for you. Not something about Biden or Hunter Biden, tell me something Trump did for you.” He gave him the whole week to think about it, and the man couldn’t come up with anything.

My dad taught me to drive—when I was thirteen, not eleven—on a rust-red stick shift Volvo DL. He didn’t mind that my mom and I painted my own first car, a green Volkswagen bug, with sunflowers on the fenders and a giant sun on the hood, but he anticipated—correctly—that I’d get pulled over a lot by the cops in our rural county. He told me I should never let the cops search my car for any reason. Make them get a warrant, he said. I asked him why go through that, since there wouldn’t be anything incriminating in there, and he said because it was my right not to be searched, and it was important to hold the line on rights. He taught my brother and me that it was necessary to vote in every single election, and to stand up for other people who were bullied and mistreated. He distrusted the bad things about our government—unjust wars, police violence—but believed strongly in the good things, like Medicare and Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act and the EPA. He sent his children to public schools, and was proud when we chose public-facing careers as teachers. The only people he was prouder of than his own children were his five grandchildren: Beatrice, Isaiah, Jesse, Harriet, and Charlotte.

Donald Terry Boggs died on March 26, 2025, in Henrico Doctors Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. Mom and Sky and I were there at the end, which was as peaceful as a hospital death can be. Even though the nurses who took care of him had only known him a little while, they loved his teasing and orneriness and sweetness. The real people of the world—nurses, dialysis techs, carpenters, mechanics, kids, and women on the side of women—all loved my dad, because he understood them and appreciated them and showed it, every chance he had.

When my mom called to tell our family friend Jason, a fellow Walkertonian, he was genuinely stunned that my dad could be gone. “He was so tough,” Jason said softly. “I was gonna bring my son by to bullshit with him on Saturday.”

My dad was tough in a way that I will never be—he fixed bad wounds (on himself) with duct tape, drove cars that didn’t have reverse, went under houses and on top of houses and in our family’s life together started many fires in a cold stove. But it isn’t his toughness that made people love him, it was his gentleness and generosity, his care for other people and belief that you should be there when a friend or family member needs you, no matter what.

When he went, my mom and I were so very surprised that he could go. The man who could fix or build anything, the most generous person we knew, was gone? We were both shaking and cold, and they wrapped us with heated blankets. One nurse held my mom, and another nurse held me. “The love is still there,” the nurse said, rocking me. “The love stays.”

They let Sky bring my parents’ beloved Yorkshire terrier, Steadman, into the room. Dad was covered with a blanket that Bea knitted, and we were allowed to stay as long as we needed. It was after two in the morning when we got back to Walkerton.

Not long after I got to bed, after three A.M., my phone rang. Who could be calling? I was so tired. The person on the other line told me she was sorry for my loss and I blurted, “Can I please call you tomorrow?” The woman apologized, and explained that her call was time-sensitive. My dad was an organ and tissue donor, and she needed to ask me questions so that his gifts could possibly be used as he intended. Oh of course, I said. Of course I could talk to her.

My father was on and off a kidney donation list for five years, during which time my mother cared for him valiantly and with good humor, as she always did for him and he always did for her, throughout their almost 52 years of marriage.

If everyone were an organ donor, like my dad was, would he have gotten a kidney before he became so sick? In our country, we have an opt-in system of organ donation, meaning you have to actively register to donate. Most democracies today have an opt-out system, meaning it’s assumed that you want to donate. A single organ donor can save eight lives, and improve the lives of many more people.

Are we still a democracy? That’s a question my dad, and Richard’s dad and so many other older people right now are not getting to see answered, not on this plane of existence. But you can honor them by voting, helping other people, holding bullies accountable, and being generous and kind to your neighbors, which sometimes means speaking up for what you believe.

You can check here to make sure you are registered as an organ donor.

You can join the April 5 Hands Off! national day of action protesting Donald Trump and Elon Musk’s unconstitutional takeover of our country and subversion of our rights. Click here to find the actions near you.

Lots of love from us.

I am so sorry for your loss. Sending you strength and peace as you and your family deal with the very difficult loss of your father. I'm sure it's a huge loss to all of you and all of Walkerton and King and Queen County.

Oh Belle, I am so sorry for your loss. You've written an amazing tribute. I know he was a great man to have raised a child like you. (((Hugs)))