After Tuesday’s post, we got a lot of emails and texts with links about octopuses (will share below!). The general consensus: octopuses are fascinating because they are smart, playful, and emotional in a way we recognize while looking and moving in a way that is extraordinarily strange to us.

“Deep Intellect: inside the mind of an octopus” by Sy Montgomery, who also wrote The Octopus Scientists and The Soul of an Octopus, explains this fascination with her trademark clarity:

I have always loved octopuses. No sci-fi alien is so startlingly strange. Here is someone who, even if she grows to one hundred pounds and stretches more than eight feet long, could still squeeze her boneless body through an opening the size of an orange; an animal whose eight arms are covered with thousands of suckers that taste as well as feel; a mollusk with a beak like a parrot and venom like a snake and a tongue covered with teeth; a creature who can shape-shift, change color, and squirt ink. But most intriguing of all, recent research indicates that octopuses are remarkably intelligent.

(I often teach this essay in undergraduate nonfiction classes because it is such a terrific example of how to explain and describe while investing a subject with feeling. Plus: octopuses! It’s octopi, Mrs. Boggs, a student once corrected me.)

The vast, mysterious, and until-recently-not-well-understood intelligence of the octopus also brings up important ethical question. Is it okay to keep them in a tank in a lab? Is it okay that some people eat them? (Octopuses are considered a delicacy in many cuisines around the world, especially in the Mediterranean and Asia.)

The tank question is tricky—scientists’ study is important for understanding them, including how to protect them. But the eating question is not hard, for two big reasons. The first is about the environmental effects of fishing and farming octopus—both terrible for our earth. The second is about the mind of the octopus—or maybe its soul.

According to this article in National Geographic, the only octopus farming venture in the U.S. is in Hawaii. Farming the octopus in aquatic pens—for reasons you might imagine—is really difficult, and Jake Conroy, the farm founder, has opened some of his farm to visitors, who can pay to see, touch, and feed the grown animals:

Conroy, a biologist who turned to aquaculture to escape the research-funding rat race, admits that such close encounters don’t encourage more consumption. “Nine times out of ten we wind up convincing people not to eat octopus,” he says. “We’re fine with that.”

Bea and I agree—don’t eat octopus!

We also watched this video of an octopus playfully interacting with a diver in Crete, and Bea went crazy:

“That would be amazing!” she said. “Being in the water! Playing with an octopus! A dream come true!”

Right now, Bea’s favorite thing is being in the water. Her other favorite thing is animals. Oh, and her other favorite thing is world mythology, in which octopuses abound!

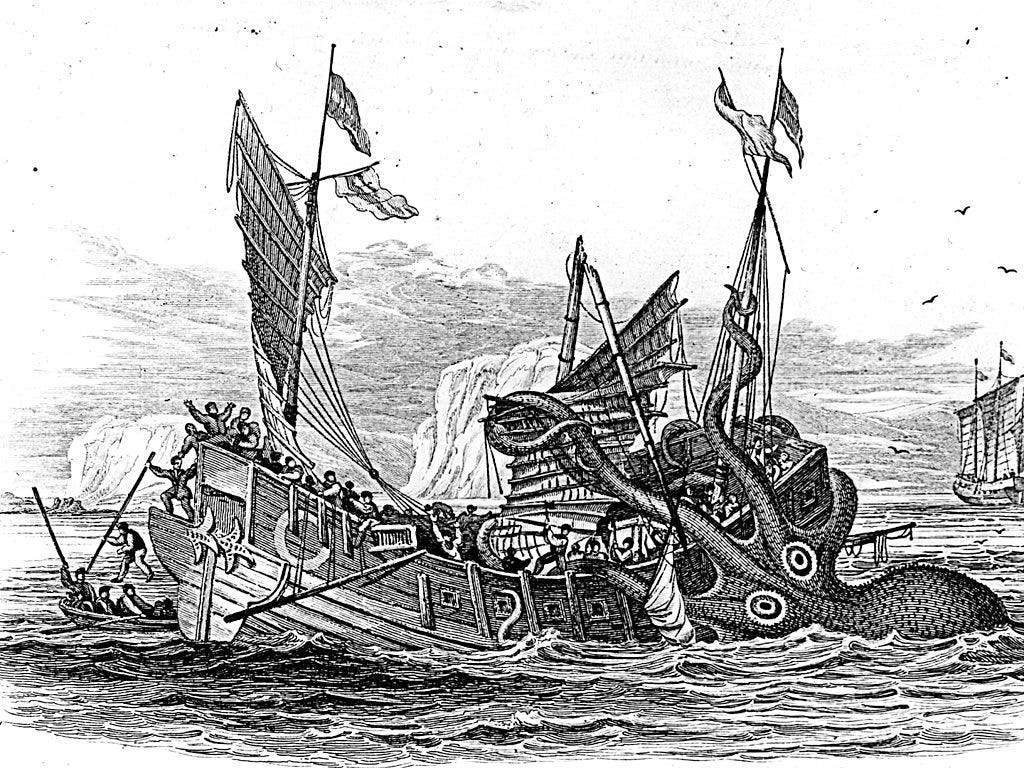

There’s the Kraken, a tentacled Nordic sea monster rumored to live in the Greenland Sea. The Old Icelandic Saga Orvar-Oddr describes the monster this way:

It is the nature of this creature to swallow men and ships, and even whales and everything else within reach. It stays submerged for days, then rears its head and nostrils above surface and stays that way at least until the change of tide. Now, that sound we just sailed through was the space between its jaws, and its nostrils and lower jaw were those rocks that appeared in the sea, while the lyngbakr was the island we saw sinking down.

In the Shinto tradition of Japan, Akkorokamui is a bright-red, part-human, part-octopus monster believed to live in the Funka Bay, and that has believed to have been sighted in other areas, including what is now Taiwan and Korea, for hundreds of years. Unlike the Kraken, Akkorokamui is a healing creature.

According to children’s book author and illustrator A.R. Jung,

The Akkorokamui is also characteristically described with the ability to self-amputate, like several octopus species, and regenerate limbs. This characteristic manifests in the belief in Shinto that Akkorokamui has healing powers. Consequently, it is believed among followers that giving offerings to Akkorokamui will heal ailments of the body, in particular, disfigurements and broken limbs.

Almost as mysterious—and perhaps the inspiration for the legend of the Kraken and the Akkorokamui—is the giant squid, an elusive cephalopod that has only been seen alive, by scientists, a handful of times, even though it can be more than 43 feet long. You have to watch this amazing video of the first filmed sighting:

This CBS News interview with Edith Widder, the marine biologist who devised the lure is also worth watching. And, in her own words, this TED talk on how they did it!

Our friend Jonathan recommends this Ezra Klein podcast interview with Alison Gopnik on why adults lose the “beginner’s mind” and the intelligence and problem solving that comes with play and exploration. She talks about the octopus, and says:

[…] I think that babies and young children are in that explore state all the time. That’s really what they’re designed to do. They’re like a different kind of creature than the adult. You sort of might think about, well, are there other ways that evolution could have solved this explore, exploit trade-off, this problem about how do you get a creature that can do things, but can also learn things really widely? And Peter Godfrey-Smith’s wonderful book — I’ve just been reading “Metazoa” — talks about the octopus. And the octopus is very puzzling because the octos don’t have a long childhood. And yet, they seem to be really smart, and they have these big brains with lots of neurons. But it also turns out that octos actually have divided brains. So they have one brain in the center in their head, and then they have another brain or maybe eight brains in each one of the tentacles. And if you actually watch what the octos do, the tentacles are out there doing the explorer thing. They’re getting information, figuring out what the water is like. And then the central head brain is doing things like saying, OK, now it’s time to squirt. Now it’s time to get food. So, my thought is that we could imagine an alternate evolutionary path by which each of us was both a child and an adult. So imagine if your arms were like your two-year-old, right? So that you are always trying to get them to stop exploring because you had to get lunch. I suspect that may be what the consciousness of an octo is like.

From all of these links and videos, what I love most is the scientist who said he prayed, please don’t leave, please don’t leave as he caught that rare glimpse of a giant squid. He knows why he is there, it must have taken many years of preparation and study to get there, but he is in that dream-come-true state that Bea imagined. His excitement appears to transcend the experience of the adult mind (full of facts and competence) and the exploratory, beginner’s mind.

Have you ever watched a wild animal with that sense of wonderment, holding your breath and thinking please don’t leave? Tell us about it!

I enjoyed this post so much! I loved the two videos. In the first one, I went crazy when the octopus seemed to snuggle with the diver. Like you Belle, I was so touched by the scientist praying, "Please don't leave," in the second one. I want to learn more about these amazing creatures! My love to all.