This week, I’ve been grateful to have a couple of notable distraction from increasingly terrifying world events. I went on a fun, splashy kayak trip with friends on Tuesday, and later in the week delightedly observed Bea’s growing enthusiasm for writing books. She finished one, and is working on another. They’re written on printer paper folded lengthwise and stapled in the center. They’re for a class of kindergartners at her school.

It has long been my belief that most kids need a sense of audience to feel motivated and invested in writing, which is by its nature kind of a hard task—physically hard for the youngest kids, but also intellectually pretty difficult in terms of translating your big thoughts and ideas into symbols on a page. Writing just for that purpose, to satisfy the question of whether you can or cannot fill the pages, read only by a teacher who slaps a sticker on top or red-pen word of praise, is inert and deflating, a sign that what you labored over, and maybe even got excited about, did not in fact translate your ideas.

This is why, when I’ve gone into schools as a teaching artist or had my own classroom, I’ve worked on building in some sort of audience for my students—we’ve made newspapers, blogs, had conversations and shared work through Wordpress sites with students in California and New York (if I had a K-12 classroom now, I’d probably use Substack to share work). We’ve given readings at bookstores for our families and published anthologies. In one third-grade classroom in Hiwassee Dam, North Carolina, students published their work on a blog while writer friends of mine were standing by remotely to leave detailed feedback, questions, and praise in the comments. The kids read every word, and laboriously hunted and pecked at the keyboards to write back.

This wasn’t my invention but something I picked up back when I was in graduate school at UC Irvine, in a public school outreach program called Humanities Out There that was founded by Professor Julia Lupton. I worked with my friend Michael Jaime-Beccera, and usually four of five undergrads, in third and fourth-grade classrooms. We worked with the kids to write poems and stories with the eventual goal of publication and sharing—in a journal (which still has a place of honor on my shelf), and online (this was before easy-to-use public platforms like Wordpress, so the actual program had to be created by computer science students at UCI). As the work appeared online, other grad students and undergrads waited back at the university to write back to our students. I remember our lessons being pretty great, but the number-one motivator for the kids was knowing that other people would eventually read and respond to their work.

Bea’s second grade teacher understands audience well. All year, Bea has brought home letters to us, letters from other kids in her class. I’ve heard about stories they’ve read aloud at celebrations. And now, some of the kids in class are writing stories that they take to the kindergarten class, read aloud (in their most expressive voices), and then donate to the kindergarten library.

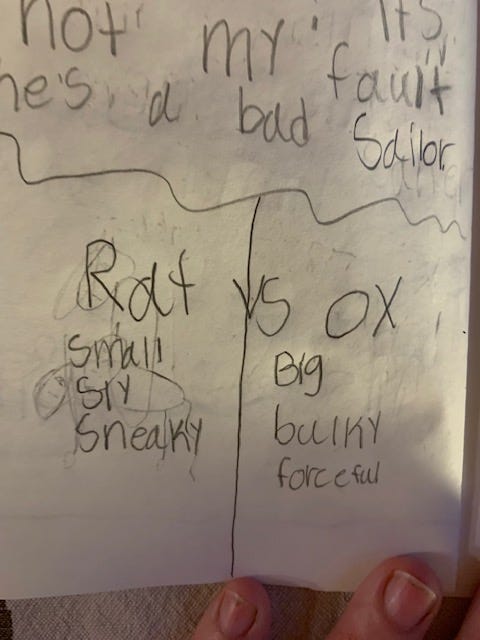

Bea’s first book was an adventurous shipwreck story called The Tale of Rat and Ox (an unlikely friendship). I could tell, as she was writing it, that she continuously thought about her audience—five and six-year-olds who might be fidgety and easily distracted, but also not quite ready for the scary stories Bea prefers. She worked hard to make it exciting and funny, but with a lesson about very different personalities finding a way to work together.

Bea was joyful I picked her up on Friday—not just because we were headed to a museum (another kind of audience-oriented display kids can create), but because the kindergarteners loved The Tale of Rat and Ox. She remembered every question they asked, all their names, and how they’d laughed or gasped at certain points in the story. “I told them that next time, I’d write them an even better story,” she said. Which is what she’s been working on all weekend, puzzling over tense and point of view and plot and clarity, and excitedly running downstairs to tell me the next part of the story.

I mentioned that this was a distraction for me, away from thinking about Putin’s war on Ukraine or my fear that expensive gas will hand the next election to autocrats in our own country. But it’s more than that, of course. Engaging teaching like what Bea’s teacher is doing and what her public school does every day is also a way for all those kids to gain confidence and an understanding that they have something to say, and people to listen and respond. Which is also why Bea and I got started with this newsletter.

We’re coming up (next month!) on the one-year anniversary of the Frog Trouble Times. It means a lot to us to have all of you (and your kids and grandkids) as readers/commenters/participants in this community. I’m hoping as we move into year two to keep the momentum going and to grow our audience, which has slowly-but-steadily increased, month by month. If you could share this post, or a recent post you liked with a friend, Bea and I would both be very grateful. We’re planning more cat posts this week, plus we both have a lot of recently-loved books to tell you about.

And did you find any four-leaf clovers this week? If not, keep looking! They’re out there! Happy first day of spring, Frog Troublers!

This gave me a lot to think about. Some of it a little bit uncomfortable, as I was raised to think that we shouldn’t want an audience. Now I see how silly that is—it’s about connection.

There is something so particularly comforting about watching children compose their own stories. Gives me hope in the world!