Y’all, I’m so tired—even mild Covid, in a healthy, vaccinated-and-boosted person (that’s me), is no joke. And without my co-writer in the room, it’s hard to make a good Tuesday post, but I’ll try!

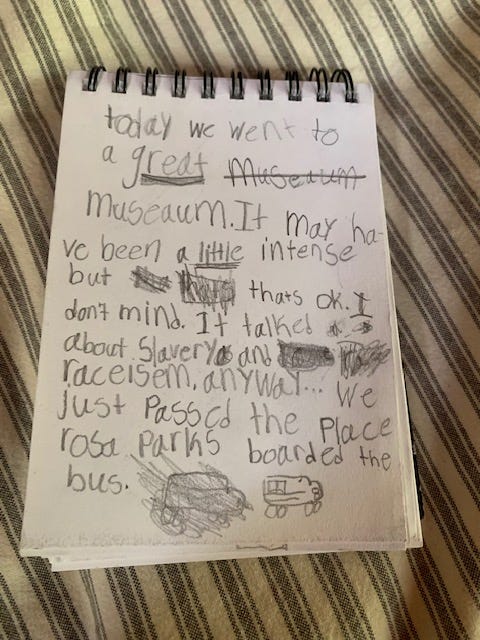

I’m writing today about museums. We visited more than a half-dozen on this trip, and I was really impressed by the museum spaces themselves—each one different in content, purpose, and resources—as well as by how well Bea took in information that was, at times, a challenge to process and interpret. Here’s a page from her bus journal after visiting the Legacy Museum in Motgomery:

Like Bea said, the museum is intense—founded by human rights advocate, attorney, and author Bryan Stevenson, it powerfully tells the story of enslavement and its aftermath in America in a 40,000 square foot space. Like many museums, the Legacy does not allow photography inside. I thought that was great, because in addition to protecting their rights, it also made for a space where everyone was in the moment, and almost no one had their phones out. The museum also wisely mirrors content in each gallery, offering the same images and words on both sides of the rooms so that you don’t have to walk in a circle or feel afraid that you missed something.

You might not feel your child is ready for a museum like Legacy—and that’s fine, of course. Harriet may be ready when she’s Bea’s age, or perhaps not yet, but I do have some thoughts about how to prepare kids for any museum visit:

1. First, do some pre-reading if you can. Bea and I read Stamped (for Kids), an adapted version of Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi. Kids will often hang onto facts better than we do, and it helps them to be able to say, “oh, I read this here…” Bea, for example, already knew the stories of the mules (Belle and Ada) that carried Dr. King’s coffin. When I asked her how, she said, “you know I read a lot of books!”

2. Get familiar with the rules of the museum. For example, do they allow photography? Bags? What’s the mask policy? All of the museums we visited in Alabama were mask-required, which I’m so thankful for now that I know some of us were carrying Covid.

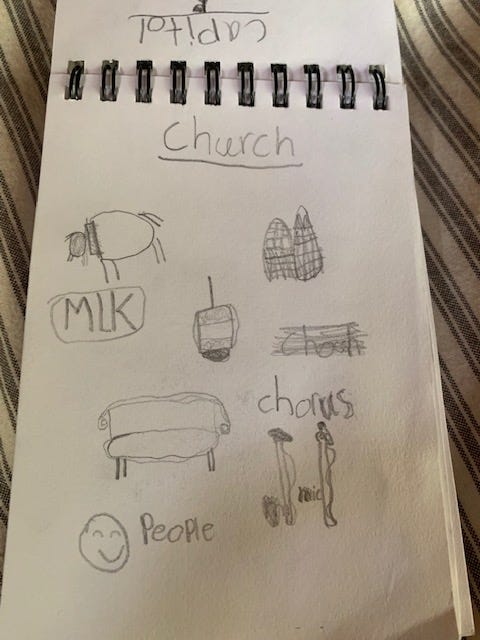

3. Give your child something to carry and touch. Bea liked having a spiral-bound notebook to record what she saw, and we always have pencils. Sometimes she wrote, and sometimes she just sketched, like this page from Dexter Avenue King Memorial Church:

4. I don’t actually like scavenger hunts or worksheets in a museum. We all process information in different ways and at different speeds, and respond to assignments in different ways. Taking a kid to a museum says you’re giving them some autonomy and respect, and allowing them to record/not record, at their own pace, shows that you mean it.

5. Mamie always encourages us to take breaks, especially in art museums, and sit with the paintings or sculptures. The Legacy Museum has a last, copper-hued space that is devoted completely to reflection—such a beautiful and appropriate choice. I saw teenagers on a school group sitting on the low sofas there, gazing at the images on the walls (not their phones).

6. It’s also great if your child can move through the museum with someone who matches their pace. Bea, it turns out, was well-matched for our new friend Dale, who uses a wheelchair. The whole time they were moving through these difficult, emotional spaces, I felt like the back of Dale’s chair, where Bea held on, was anchoring her.

What advice do you have for a museum visit, especially with kids?

Another thing this trip brought up for me, which I’d almost forgotten, was how a museum in Selma (the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute) inspired a project I did with students years ago in Durham. I worked at the Central Park School, a project-based charter, and in spring 2008 (a historic year, it turned out!) we studied voting rights in America. We read about Selma’s museum, and must have researched their exhibits online. From there, we researched voting rights heroes in North Carolina and beyond, learned about the poll tax and literacy tests created to deny Black people their right to vote, and made connections to contemporary voting rights—and obstacles. For our culminating project, we built our own temporary voting rights museum in a public building near the school.

I still think this is an excellent thing to do with a class of kids, whatever they are studying. Here are my suggestions for building a pop-up museum space:

1. If possible, visit a museum with the class first. Ask kids to notice how information is conveyed—is it all reading? Or is some of the experience active, auditory, or visual? You might even talk to a museum educator or someone who works in museum design—we actually had one on our trip!

2. Begin building the museum after you’ve completed your study. The supplies we used for our voting rights museum were humble ones—paper, black and white watercolor, cardboard, markers. Our fanciest item was a digital voice recorder for our memories booth, but that could also be done on a borrowed laptop or tablet. Pro tip: if you mat your drawings on black construction paper, they look a thousand times more polished!

3. Break into teams to get the work done. Some ideas include: a portrait gallery team, museum placard team, a team for experiential learning, a team for recording stories. At our voting rights museum, we recorded stories from our visitors (mostly parents and grandparents) about their memories of their first time voting.

4. Finally, invite others, and allow the kids to station themselves throughout the space as docents and guards. You can even make a museum shop (I don’t think we did this, but if you did you could sell bookmarks, pens, even small postcard replicas of the portraits.

Have you ever made a temporary museum or gallery? How did it go? What’s inspiring you these days, Frog Troublers?

Oh, and I forgot to say: we'll share the embroidery on Friday!

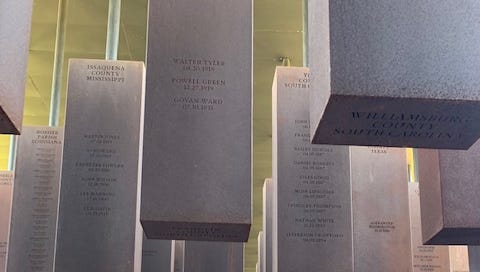

I visited Selma as well as nearby Gee's Bend, aka Boykin, which is in Wilcox County, which offers a vivid illustration that, while things have gotten somewhat better in that part of the world, they are not all the way better. To wit: Gee's Bend, which is known for the unique and beautiful work of its quilters, is situated in a bend of the Alabama River, which separates it from the county seat of Camden. Gee's Bend is 95% black. In order to vote, the people of Gee's Bend take the ferry to Camden, which makes the trip 8 miles versus 38 miles to the nearest bridge and back. Unfortunately, somehow, the ferry frequently goes out of service right around election time. There's a lot of work still to do when it comes to equity in Alabama (and the broader South), and it is places like the Peace and Justice Memorial that remind us that we can make a difference, despite the odds stacked against... peace and justice.